Last week I received peer reviewer comments for a chapter I have in an edited collection as well as an article a friend generously looked at after I got a journal rejection. It got me thinking about the disconnect that often occurs between how we teach students writing works and how professional writers, in this case academics, write and respond. This was already bouncing around in my head because the week before last a student asked me to look at a piece of writing in a way that I imagine most of us don't hear as often as we want. The student had turned in a paper, but for personal growth had a question about a section, how best to transition, revise it, their sense was that this bit seemed off. So I was happy to read it, and offer some comments on how to revise, an approach, that also expanded the section and talked about why this felt off, and some fixes. The student mentioned that this was the type of help they had hoped X class would serve.

So I was thinking about how I teach writing, and how I can approach writing differently in my upper level classes. Because I do grade conferences in my composition classes we look at genre, define it, talk about rhetorical situations, read and analyze mentor texts, and talk about what elements THEIR versions of X genres should include. In these classes I focus on how well their piece of writing conforms to X genre, how successfully they cover the elements, then if they go further with creativity or revision. They get to choose their own topics and I focus a lot on them discovering their voice and exploring their interests. When we grade conference they tell me based on this class work and discussion what grade their work earned and why. I tell them what I love about it, what struck me, I ask questions as a reader, what I didn't understand or wanted more of. Then we use that to work on feedback.

I do something similar in my upper level classes with grade conferences and feedback. But I've redesigned these classes to cover more skills- so each class has a close reading paper, an unessay, a final paper, then some form of scholarly response. They still get to pick their ow topics, explore their own interests, but I want to make sure each class is reinforcing these key skills. So I think I want to spend more time talking about writing. Thinking of the two sets of notes I got on the article that was rejected, which both provide VERY different feedback (one from outside the field, one from an expert), and the notes on the edited collection, I thought that I'd use these pieces with my students. I want to share how we get feedback, and how the "fix these things, but I won't tell you how" notes are very different from how we usually tell students how to shape their writing.

I think too that me trying to get students to like writer's notebooks is about all this as well- my notebooks are my main lifeline, they are key to my process, and I really wanted to challenge students to explore that, stretch themselves and try something new. They hate them. I have tried different forms, they hate them all. But I think that I have a new way to try and accomplish and share what I'd like.

Keith Thomas' 2010 "Working Methods" about how he writes was making the rounds on Twitter over the weekend. It was the first time I had seen it and I really enjoyed it, particularly the tactile references within the piece and in the responses to the Tweet. As much as I love technology, draft in Google Docs, blog, and Tweet about my work, my process is grounded in a series of paper notebooks (no longer 100s of empty ones guilting me about not using them now that I use them all for writer's notebooks), color coded paper notes, Post-Its, multi-colored scribbles.

So I think what I'll do with my upper level classes, as well as in my Intro to English Studies and Capstone classes, is share what process is AND present it as a way to address these more holistic comments of these were the issues, you figure out how to fix.

So here is a brief overview of how I write. In general, ideas for chapters and articles and blog posts all start in the writer's notebook. Depending on the idea sometimes this is a short web, sometimes it's more detailed.

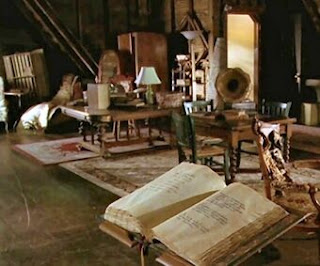

|

This page became a CFP for an edited collection. Sometimes these notes then become a blog post which allows me to write through my thoughts. This is often where the structure emerges along with what I actually want to talk about. The next step is a relatively new one. I never used to outline, but on dissertation #2, outlining was one of the things my director recommended. Actually she recommended and showed me how in Word, to use outline view, where you can just see the first sentence in your paragraphs. It's a great way in especially larger works to see if your organization is working or running off the rails. It was during my work on dissertation #2 that I started outlining all my work. I start with a rough outline, then I leave it, and add more to it as it occurs to me.

This is another thing that I mentioned to the student from the beginning of this piece- that some revision only becomes clear with time to step away and come back, time to let ideas marinate, which undergrad classes do not always allow. Time is a luxury and a privilege, certainly a fact academics know, precarity robs many of this time as well as access, there is no protection or assurance of it.

When I'm ready to start drafting I put my outline on book desk stand so I can see it as I draft AND use the outline as my template, just file --> make a copy in Google Docs so I write with that in mind. I write my analysis first. I was taught that academics write conference presentations first because the genre focuses on THEIR argument and that's the idea I stick with. Once I have my thoughts, my analysis, which tends to be a close reading, I then start with research. I log onto the library and search articles and ebooks, things that are accessible. Many times there are articles that seem cool and I probably could use but my university does not have access to so I can't use. I print these out because I can't read and understand the way I need to electronically. I also use books. When I was at a larger university I used ILL and the library itself all the time. Our library here is mostly in storage due to renovation plans so not ideal. In both cases I have also bought books. For this edited collection there's a brand new book out on my topic for my chapter, like just perfect, so I ordered it for $119, which honestly, is FAR beyond what I can afford/what I normally buy. My medieval and early modern books tend to be more expensive than my horror or fairy tale books. When buying, I default to dissertation logic- is this a book that I can use down the road both in my scholarship and teaching? If the answer is yes I buy it.

Once I've read all my scholarship, I go back to my draft and read it over, hard copy, printed out. I make notes both on the draft, in a nice, easy to see difference, colored pen, and on legal pad for larger additions/changes. I also physically cut pages and use a glue stick to paste items back. I try to then set this aside. The next time I write I type up all these revisions. I've learned there is a magic time between wanting some distance so I can see things clearly and waiting too long and not understanding whatever code I wrote revision notes in. When I was working on the PhD I made writing a habit. I sat at my desk every morning after walking Nehi, ate lunch at my desk, and was there until 4p. Some days I got a lot done and some days I just sat there staring at the monitor, mostly on Twitter. But even on these days because I knew I wasn't "allowed" to leave my desk or office, I ended up getting stuff done, even if it was the more minor stuff that allows and contributes to writing even if it's note ACTUAL writing.

Back to time as a luxury, now with a full time job, this is not my schedule, and this is not a bad thing because one of the things the diss 1, diss 2 situation taught me was the consequences of forcing writing. For me there's a fine balance between making writing a habit and not forcing ideas that you'll end up having to just junk and rewrite. I agree with others that Tweeting about my work and blogging about teaching and scholarship made diss writing (especially the second time) easier. When I was teaching high school full time, when I had scholarly stuff I was working on, I set aside Saturdays for whatever I needed. I'd set aside the whole day for reading, drafting, whatever I needed. This last year, my first at a new job, had a steep learning curve, so things were more piecemeal. I got one chapter done over summer after moving, before school started. Then had revisions for that chapter and proofs for another over the fall. Over winter break I wrote an article and submitted it before we were back. I had planned on redoing the book proposal over spring break but because of the pandemic that got tossed. I've found that my schedule just does not allow for my scholarly Saturdays. I often have events, I spend most of Sunday lesson planning for the week, so I really need my Saturdays off. So, what seems to work is only writing or revising on breaks, so over the summer, fall break is really just a long weekend, but Thanksgiving works, as does winter break, and normally spring break. Knowing this I need to plot out how to get stuff done which means having a clear research agenda and set of ideas.

This schedule helps me because it means I can set a timeline that ensures things get done, that I have articles or chapters in various forms of submission, and I don't feel stressed when I DO have to work on weekends or things come up. This summer I want to get the edited collection I'm co-editing sorted, so get the introduction drafted with my partner in crime, research and write MY chapter for this so it's done, and set the TOC so folks can start their writing. I'd like to also revise my Guthlac article and send it back out AND redo the book proposal and get that sent out. That last may be too ambitious as it also means rewriting a sample chapter, but those are my goals.

When I get notes and revisions back I try and knock them out right away so that they're off my desk and so they don't get short-thrift as stuff comes up later.

I am still feeling rocky about balance with my new job and how to stagger articles and chapters so I'm always working on one thing, have another submitted and waiting to hear, and then one going to print. Of course all this is influenced by fact that I haven't presented at conferences in a couple years because of high school teaching then this transition and will not be for the foreseeable future so all my ideas are fresh out of my head. I am lucky that my new job requires 3 peer reviewed texts for tenure, and after my first year I have one published, one coming out end of this year/beginning of next, so I think I'm on track to be okay, but it is all new.

Anyway, that's how I write, and I hope sharing this with my students, the process in general, and some my of my specific tactics, will help.