Presentation for International Congress of Medieval Studies

Kalamazoo, Michigan

Thursday 11 May 130p Schneider 1360

The full presentation can be found here.

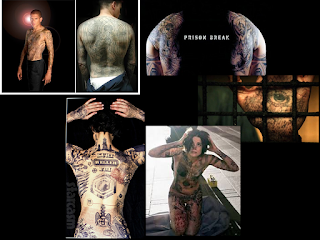

The last few years have seen a normalizing of the heavily tattooed. In shows such as Prison Break (both its initial run from 2005-2009, and its revival this month) and Blindspot (from 2015 to now), the lead characters are not just heavily tattooed, but their tattoos tell a narrative that is key to the plot.

In addition to popular culture, in the last few years medieval studies has shown an interest in tattoos, from researching the connection between pilgrimages and tattoos

to understanding the place tattoos had in The Crusades.

In each of these cases, the idea that tattoos represent experiences and tell a story is key.

The idea for this roundtable came out of a Twitter conversation where many of us (medievalists) shared our tattoos, both as medievalists with tattoos, and people with medieval-inspired tattoos. This resulted in a great Tumblr- Bad Ass Medievalist Tattoos.

This also got me thinking about the overlap between these two ideas. Specifically, I started to think about how to current sociology scholarship that dealt with heavily tattooed women could be applied to medieval female saints' lives.

Modern sociology scholarship on tattoos that focuses on women tends to focus on the male gaze, sexualization of women's bodies, how heavily tattooed women are viewed, and less so, how heavily tattooed women feel about these issues.

This got me thinking- what happens if I applied modern day sociology scholarship on heavily tattooed women to the hagiographies of female saints lives?

This scholarship generally considers the way heavily tattooed women are considered to:

- cross a socially accepted line

- violate gender norms

- and perform a narrative publicly

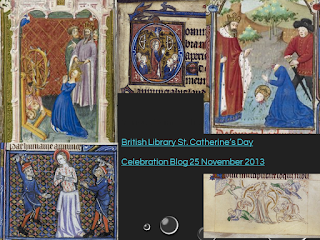

In hagiographies, women testify, in public forums, but just as often, in addition to this, they perform their faith in public venues through the tortures they endure. These tortures are both evidence of their faith and in the eyes of their persecutors, punishment for their disbelief.

We see this presentation of torture as another form of testament and performance in Saint Katherine's narrative.

We see this aspect of performativity in manuscript images that focus on Katherine's tortures, the wheel she was supposed to be tortured on, and her beheading- literally the removal of the means by which she conveyed her narrative.

If we overlay Katherine's performance of faith over the sociology of tattoos, we can see they line up.

I have a full back piece that tells the narrative of my PhD process from 2015 to now:

- I took my comps in February 2015, so I started my back tattoo on 14 February

- As I finished comps I got the next part

- 5 March 2015 I defended my prospectus, so 8 March I added another piece

- Then finished that piece on 18 March

- As I completed an entire draft of the original dissertation, I added more on 23 October 2015.

- By 26 July 2016 I had just learned that I would not be defending or graduating, and had to throw the whole dissertation out and start over. So the back got outlined in red.

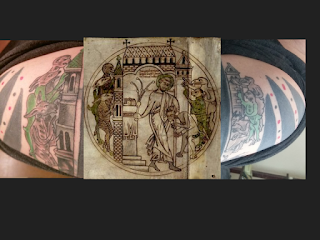

The armbands stylisticaly tie into the back piece, connecting previously unrelated narratives.

They also feature work foundational to my approach in the dissertation- the Guthlac Roll and the Story of Guthlac A and B, where demons represent national interests and challenge the narrative of English national identity. I also added gargoyles inspired by Notre Dame.

For the Guthlac demons, my tattoo artist worked right off the manuscript images, copying the little guys perfectly.

Looking at my narratives through a sociology lens, the narrative of my tattoos:

- Crossed a line when I decided to become heavily tattooed with a full back piece

- Violates gender norms as women are not supposed to be heavily tattooed

- While my tattoos are often seen as a public performance of identity, this is not always true. Amongst like minded people, yes, it's a shared experience, shared narrative. My tattoos are performative in nature, telling multiple, layered stories, although I have found that the more heavily tattooed I am, the less I display them, which is in line with what sociology studies have shown.

Moving forward, I plan on expanding my reading of narratives of the Katherine Group through this sociological lens, as I think the intersection between torture as narrative, performativity, and gender expectations, will provide interesting insights.

Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment